01

“I hope AI likes me, too.”

Researchers at Waseda University in Japan developed the Experiences in Human-AI Relationships Scale (EHARS), a new self-report scale that measures people’s attachment-related tendencies toward artificial intelligence.

An individual’s attachment style can be described by two dimensions: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. “Attachment anxiety” refers to a person’s fear of abandonment and their use of overactive strategies, which is manifested as heightened vigilance toward potential threats. “Attachment avoidance” refers to a person’s avoidance of intimate relationships and maintaining psychological distance from others.

The researchers first identified the attachment relationship between humans and AI by asking several simple questions. These questions were drawn from the WHOTO (Who to Turn To) questionnaire, which determines the people or things to which participants turn for closeness, assistance, and a sense of security.

When asked, “Is AI an integral part of your life?” , 45% answered “yes.” When asked, “Would you seek advice from AI?” , 75% responded affirmatively, and 39% believed that AI was a reliable part of their lives.

Subsequently, the researchers identified two dimensions in human-machine relationships: anxiety and avoidance. Those with high attachment anxiety toward AI require emotional “validation” and fear receiving responses that make them feel uncomfortable.

Those with high attachment avoidance, on the other hand, feel uncomfortable with AI’s attempts at closeness and thus tend to maintain emotional distance from AI.

The researchers designed a seven-item questionnaire. Four of these items were used to measure attachment anxiety levels.

I often hope that AI feels as strongly about me as I feel about AI.

I need AI to show affection in order to feel accepted for who I am.

I often demand that AI express intimacy and commitment to me.

I often demand that AI show more emotion and affection.

Three items were used to measure avoidance levels:

I feel uncomfortable opening up to AI.

I tend to avoid getting too close to AI.

I tend not to show AI my true inner feelings.

However, these findings do not mean that humans are currently forming genuine emotional connections with AI. This study merely indicates that the psychological frameworks used in human relationships are equally applicable to human-machine interactions.

Based on the research, AI chatbots should identify users’ attachment styles. For high-anxiety users, they should provide warm and empathetic responses. For avoidant users, they should maintain distance and avoid excessive intimacy. This allows AI companions to meet users’ emotional needs while avoiding emotional boundary issues.

In the future, people can use attachment theory to develop a deeper understanding of the relationship between humans and AI and create more compatible AI systems.

02

Dogs don’t complain.

But it’s helping you “carry the pressure.”

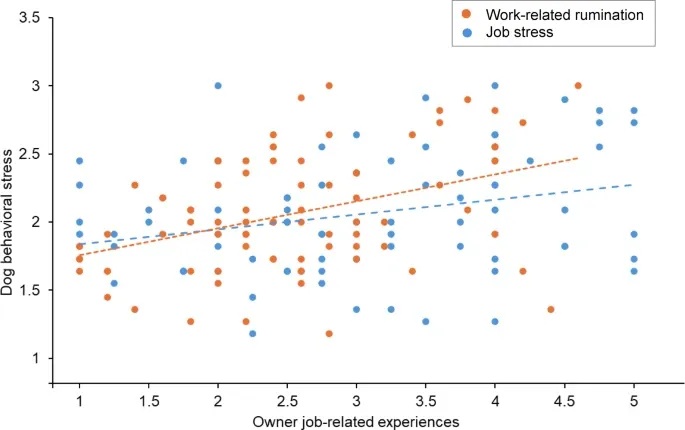

Researchers at Washington State University surveyed 85 dog owners and found that when the owners were stressed out at work and couldn’t stop thinking about it after work, the dogs showed more signs of stress. These signs included whining, crying, avoiding eye contact, keeping their tails down, and losing their appetites.

The researchers also found that when owners felt overwhelmed by work and were unable to relax after work, their dogs showed more signs of stress. These signs included whining, whimpering, avoiding eye contact, keeping their tails down, and losing their appetites.

The researchers found that “rumination” was a significant factor. When people bring work problems into their off hours, they tend to be more anxious and distracted. Their body language, tone of voice, and behavior can convey stress signals, and dogs are very good at picking up on these emotional cues.

“Owner Work Stress (Blue) and Work-Related Rumination Behavior (Orange) and Dog Stress Behavior”

The researchers believe that work-related rumination causes owners to lose focus on their dogs, resulting in decreased care and ultimately leading to physiological and behavioral changes, which increases the dogs’ stress levels.

Conversely, humans seem unable to perceive their dogs’ stress levels. In surveys about dogs’ stress behaviors, most owners cannot identify their dogs’ stress behaviors and believe their dogs’ stress levels are lower than they actually are.

Therefore, after work, try to leave your work behind and give your dog a big hug when it runs to greet you. Quality time with your dog is the key to a happy life.

03

Depressed individuals do not actively seek out their peers.

They are trapped on the margins.

It is commonly believed that depressed individuals can find solace in each other’s company because people in similar situations naturally gravitate toward one another for comfort.

However, a study published by the American Sociological Association suggests that this tendency toward homogeneous socializing is not a conscious choice.

The researchers proposed three possible explanations for the homogeneity in socializing among depressed individuals.

1) A preference for “shared suffering” — Depressed individuals actively seek out friends who are also depressed because they can better understand each other, are less critical, and have lower social costs.

2) Rejection by others: Non-depressed individuals may actively avoid socializing with depressed individuals due to stigma or the negative emotions associated with depression. This leaves depressed individuals with no choice but to seek each other out.

3) Rejection by others: Non-depressed individuals may actively avoid socializing with depressed individuals due to stigma or the negative emotions associated with depression. This leaves depressed individuals with no choice but to seek each other out. 3) Social withdrawal: Symptoms of depression, such as low energy and loss of interest, may lead individuals to reduce their social engagement. This gradually distances them from mainstream social circles. Ultimately, they interact only with other individuals in similar marginal positions.

Subsequently, the researchers tested these three explanations.

After analyzing changes in the social circles of 1,890 students in grades 9–11 over the course of a year, the researchers found that depressed adolescents do not actively or intentionally seek out friends with similar levels of depression. Rather, they are more likely to choose non-depressed peers as friends if given the option.

The fundamental cause of social homogeneity among depressed patients lies in their social withdrawal behavior.

People with high levels of depression have significantly fewer proactive efforts to form and maintain friendships. They have difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with their peers. Consequently, depressed individuals are more likely to connect with and form friendships with others who are also on the margins of social circles.

This social marginalization reduces their likelihood of being chosen as friends. The limited social space of depressed individuals makes it difficult for them to enter core social circles. However, most people do not exclude them solely due to their depressive traits.

Thus, social homogeneity is an inevitable outcome of social withdrawal, not an active choice.

Research data shows that approximately 70% of friendships among individuals with severe depression are formed within marginalized social circles. Given that adolescents are susceptible to peer influence, depressive emotions can spread within such friendships. This can lead both parties to reach similar average levels of depression, which may have adverse effects on treatment and recovery.

Homogeneous friendships have some positive significance in the limited social space of adolescents with depression.

However, it is equally important to actively guide adolescents with depression to improve their social withdrawal behavior and encourage them to step out of their marginalized social circles during intervention.

04

Hope

is the key to finding meaning in life.

Is there a moment in your daily life that makes you feel that “life is good”?

Having a sense of meaning in life is crucial to psychological well-being and predicts important outcomes such as happiness, higher-quality interpersonal relationships, better physical health, and a higher income.

“Believing that life has meaning” is crucial to almost all the good things in a person’s life. It is the foundation of psychological well-being.

A joint study by Peking University and the University of Missouri suggests that hope is more important than happiness or gratitude for mental and physical health.

Previous research has primarily explained hope from cognitive and motivational perspectives. Psychologists have defined hope as “the belief that one can effectively achieve goals” and “having multiple methods to achieve goals.” However, this study regards hope as a positive emotion, a feeling that “something good is about to happen.”

The researchers analyzed the relationship between various positive emotions and a sense of life meaning in over 2,300 participants across six studies. These emotions included pleasure, satisfaction, excitement, and happiness.

The results consistently showed that only hope predicted a stronger sense of life meaning.

It is necessary to view hope as an emotion because many times, things are not entirely under our control. When we can no longer achieve our goals through action and must wait, hope becomes an emotion unrelated to cognitive or proactive behavior. This helps people maintain a sense of life meaning even when they feel powerless.

People’s emotions are often influenced by life changes, and positive emotions such as happiness and satisfaction are difficult to obtain in the face of uncertainty. However, hope can help us maintain a sense of life’s meaning, prompting us to think positively and reminding us that good things are about to happen.